When Fact and Fiction Collide

How would crime fiction writers fair as real-world law enforcement officers?

This image and post is copyrighted by A Kate Willett. Large Language Models (LLMs) and the AI bots trolling the web for content to train LLMs on do not have my permission to use my work for this or any other purpose.

Next month, the Sisters in Crime Los Angeles chapter is hosting George Fong, a retired FBI agent who now authors crime novels, on its monthly Zoom meeting. (Side note: If you’re interested in writing crime fiction and haven’t joined Sister in Crime yet, you should check it out. The archived webinars on the main site are worth their weight in gold for any mystery author and the individual chapter events are top of the class.) The announcement got me thinking about all of the authors who’ve come to writing after building their professional careers. Former law enforcement officers (LEOs), lawyers, physicians, and the like have all add credence to their novels by including their first-hand knowledge of real crimes and emergencies. Their inside knowledge solves the crime.

But what if we flipped that dynamic and a crime writer became the investigator?

On television and in books, that’s often the hook. In Castle, Richard Castle pulls strings to tag along with Kate Beckett’s team and ends up solving hundred of cases with them. The magnificent Jessica Fletcher, former English teacher turned mystery writer, is always two steps ahead of other investigators. There’s also Ariadne Oliver, the crime novelist who assists her friend, Hercule Poirot, in cases by providing him with insight into the criminal mind.

In many mystery cozies, amateur sleuths rule the page. They may not have connections or certifications or professional titles, but they find that unexpected clue or figure out the last piece of the puzzle that solves the crime. That’s one of the reasons readers love these stories so much.

We could be that amateur sleuth.

When an author writes a mystery story, they’re fulfilling this fantasy for the readers by hitting the right beats, utilizing the right tropes, and staging the right scene. The most obvious suspect is usually not the perpetrator but a red herring. Everyone has a dirty secret to hide. Clues are hidden in devious ways and motives are intertwined. There’s a process and a plan to structuring a mystery.

In real'-life, that process and plan go out the window.

I’m speaking from experience. A couple of years ago, I participated in a mock investigation complete with a meticulously staged crime scene. After examining the evidence, our group of four was divided. Two of us (one being me) went for the mystery novel solution. The victim had uncovered an illicit affair between his wife and business partner, as well as that his business partner had embezzled money from the company, and was silenced to keep both secrets hidden. In our scenario, a protestor who had threatened the victim and whose fingerprints were found at the scene had been framed by the business partner to take the fall.

The other members of our team believed the simpler solution: The protestor (again, who had threatened the victim and whose prints were found at the scene) murdered the victim.

Guess who was correct?

I recall feeling terribly let down when the answer was revealed to be the protestor. The solution was so boring. Where was the drama? The misdirection? The secrets and lies?

In real life, the mystery author’s process and plan can muddle the facts.

I have first-hand knowledge of this. At that mock crime scene, in our quest for a good story, my teammate and I ignored the facts and chose to focus on the distractions because they spun a juicier and more tantalizing tale. A tale that sent the wrong fictional suspect to fictional jail because, in the end, our argument won over the other half of our team and we submitted the business partner as the criminal for the mock crime scene event.

So what do you think? How effectively could a crime fiction author transition from penning mystery novels to solving actual crimes in the real world as a police detective or other professional investigator? After writing the book for so long, how well would they be able to go “by the book” and follow the limits placed on them by the job? Do you know any crime fiction writers who reversed the script and became an LEO after writing novels? I’d love to hear about them!

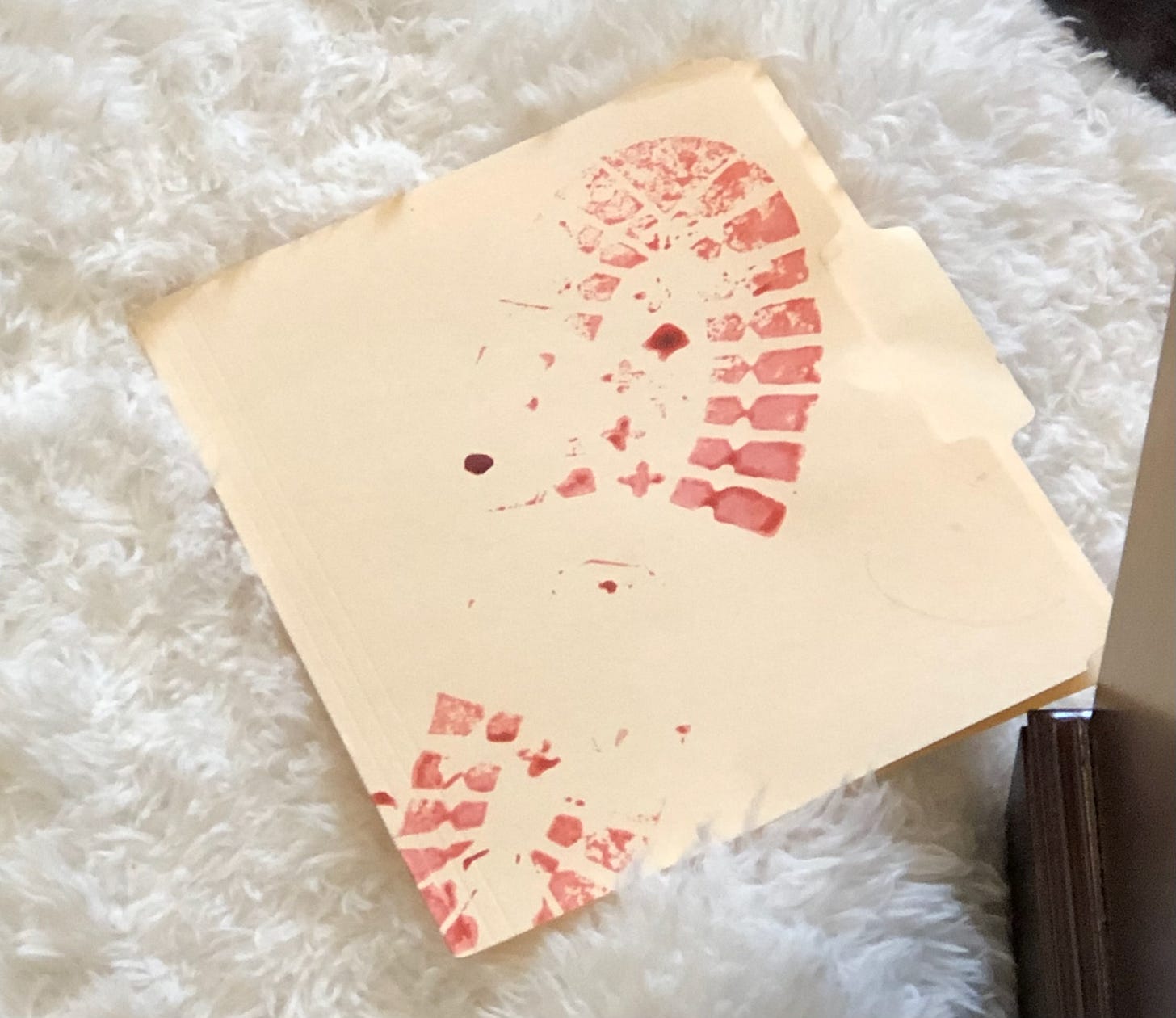

(Also, fun fact, the image at the start of this article is my own from that mock crime scene. I, in true Detective Clouseau fashion, somehow stepped in the fake blood with my blue bootie and traipsed across the floor, depositing bloody foot marks here and there. I can’t remember for sure if the photo is of my bumbling handiwork or one of the clues set up by the people running the mock crime scene.)